Hilary Tyler, 21 June 2019

Note: This article contains distressing data about the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Northern Territory.

In 2007 the federal Intervention, together with the NT government’s dismantling of community councils in Aboriginal communities, combined to strip away Aboriginal people’s autonomy at both the individual and community level. The Intervention was later rebranded ‘Stronger Futures’ by the Labor federal government, with minimal changes made.

The Intervention took control of Aboriginal land, brought in the Basics Card which controlled people’s welfare payments and what they could spend their money on, inserted “Government Business Managers’ into communities, dismantled CDEP and replaced it with ‘work for the dole’, discarded the permit system, controlled who can operate a community store, banned alcohol and pornography in communities (further demonising Aboriginal men particularly) and legislated that customary law cannot be taken into consideration in determining bail or sentencing.

The replacement of community councils by the NT government with ‘MegaShires’, run by non-Aboriginal people from far away, inserted external control into the lives of people living remotely.

The federal Intervention and the creation of MegaShires have together ripped control from people and continued the colonial diatribe that Aboriginal people are incapable of managing their own affairs.

The federal government stated that the Intervention was to

- protect children and make communities safe, and

- create a better future for Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory.

So how has it gone? Has there been an improvement in the lives of people in the NT in the last twelve years? Or has it been an abject failure?

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) published the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework of 2017.[1] It found that over the past 10 years Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the NT have worsening health, with a widening gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous, and worse health compared to other Indigenous people in Australia.

The following data is from this report.

Life expectancy: In the NT, the gap in life expectancy at birth between 2007 and 2012 increased from 14 to 14.4 years, while the gap nationally decreased. During this time, the life expectancy for Indigenous NT females FELL from 69.4 to 68.7 years.

Infant and child mortality: While infant and child mortality remains higher in the NT amongst Indigenous populations, the gap is closing both in the NT and nationally. Wow, we have a success! We note, however, that while perinatal mortality (deaths in the womb, and up to 1 month old) has continued to decrease nationally amongst Indigenous populations, in the NT this rate has remained static between 2006 and 2015.

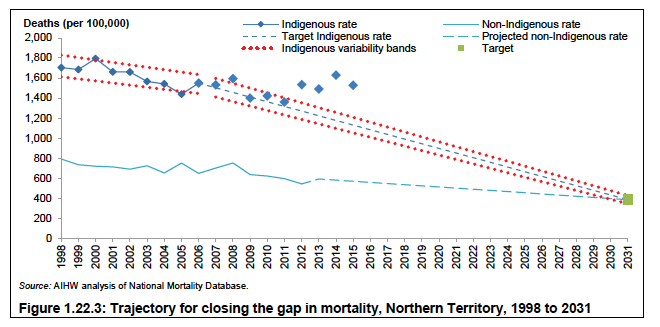

All-cause mortality: The gap in ‘All cause age-standardised deaths’ has not changed either nationally or in the NT. While the NT was on trajectory to close the gap until 2011, this has now changed.

Low birth weight: The gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous low birth rates in the NT is not improving, while nationally there is a closing of the gap.

Hospitalisations: Hospitalisation rates in the NT are increasing for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people; however, there is no decrease in the gap between the two. Specifically, the gap in the NT is widening for hospitalisations for injury, respiratory disease and circulatory disease.

Acute rheumatic fever: is a leading cause of heart disease in Indigenous populations in the NT, and is largely unseen in the non-Indigenous populations (98% of cases are seen in Indigenous people). It is a consequence of overcrowding in sub-standard housing. In the NT the rate has continued to increase, more than doubling between 2010 and 2015. Nationally there was a small increase in the rate amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This following quote from 2007 remains saddening:

“It is unlikely that such a stark contrast between two populations living within the same national barriers exists for any other disease or on any other continent”[2]

Diabetes: is a disease of poverty. The rate of diabetes in Indigenous people in Australia is the highest in the NT.

Kidney disease: 40% of Indigenous adults in the NT have chronic kidney disease. Between 1996 and 2014 the rate of End Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) in Indigenous people in the NT increased from 73 per 100,000 to 140 per 100,000, while nationally the rate in Indigenous people increased from 22 to 36 per 100,000. The age-standardised incidence rate of treated ESKD for Indigenous people in the NT was 26 times the rate for non-Indigenous people.

Dental disease: in Indigenous children has remained the same in the NT, despite the massive input of resources, while nationally it has decreased.

Risky alcohol consumption: Age-standardised hospitalisation rates related to alcohol use more than doubled in the NT for Indigenous people between 2005 and 2015, compared to no change for non-Indigenous people in the NT, and a small increase for Indigenous people nationally.

Mental health admissions: more than doubled for Indigenous people in the NT between 2005 and 2015, compared to no change for non-Indigenous people in the NT, and a smaller increase for Indigenous people nationally.

Self-assessment of health: It is not surprising therefore that the proportion of Indigenous adults in the NT who assessed their health as excellent/very good decreased between 2002 and 2015, whereas nationally the proportions remained stable.

The determinants of health include autonomy, housing, employment, wealth, and education.

AUTONOMY: We have described already how autonomy has been ripped from peoples’ lives, both at a community and individual level.

HOUSING: is important to people’s health in many ways. In the NT, there are the highest reported rates in the world of diseases such as rheumatic fever, rheumatic heart disease, bronchiectasis, post-streptococcal kidney disease, and glue ear. These diseases are a direct result of overcrowding in substandard housing.

AIHW reports that in 2015 46% of Indigenous people in the NT lived in government housing. 53% lived in overcrowded housing, compared to 8.7% of non-Indigenous people and 21% of Indigenous people nationally. There has been a decrease in those who report they live in overcrowded housing from 66% in 2005. However more Indigenous households live in houses of an unacceptable standard in the NT in 2015 compared to 2008.

EDUCATION: Education is a key determinant of the future health of a population. The dismantling of bilingual education by the NT government in 2009[3], as well as the Intervention related SEAM programme (ceased 2017) which allowed suspension of parents’ welfare payments if their children didn’t attend school[4], have both negatively impacted on school attendance and the wellbeing of communities.

In 2015 only 30% of Indigenous adults in the NT aged 20-24 reported that they had attained Year 12 or Cert II or above, compared to 62% of Indigenous adults nationally. Less children are going to school compared to before the Intervention, and attendance rates for Indigenous students in the NT are the worst in the country.[5] [6] [7]

EMPLOYMENT is another key determinant of health. According to the Australian government[8], in the 10 years after the Intervention employment of Indigenous adults fell, and unemployment rose. This is despite the government excluding from these figures those who were working in CDEP before the Intervention. CDEP was progressively dismantled in the years after the Intervention. However in the decades it existed, it allowed flexibility in work hours and top up wages, and promoted service provision in communities that since its cessation have not been funded. Research demonstrated improved socio-economic outcomes on a range of measures[9] compared to those unemployed. Now, in Work for the Dole schemes that have replaced CDEP, participants must work longer hours, with increased penalties such as welfare payments being withheld if hours are not worked. As a consequence there are now significant numbers of people who are receiving no payments at all, increasing the financial vulnerability of both individuals and families who are supporting these people. In the NT in 2015 37% of the Indigenous working age population reported they were employed (23%FT, 14% PT), compared to 83% of the non-Indigenous population in the NT, and 48% of the Indigenous population nationally[10].

INCOME: There is growing evidence that Indigenous people living in remote communities in the NT have become more deeply impoverished since the Intervention[11]. Over the past decade adult median income has dropped significantly, and people who survived with income under the poverty line in 2006 are now deeper in poverty after 10 years of Intervention[12]. The economic disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous community members has also increased: from 4.8 to 5.9 times at Papunya and 3.1 to 6.9 times at Maningrida. At the same time, the census indicates that poor Indigenous community members are paying more rent than relatively well-off non-Indigenous people.[13]

“The decline in median personal income everywhere provides hard evidence that the abolition of the Community Development Employment Projects scheme has been an unmitigated disaster redirecting people from part-time community-managed waged work to below award, externally monitored work-for-the-dole that more deeply impoverishes the jobless.” Altman[14]

Furthermore, income management – ‘the Basics card’ – has not been beneficial, as indicated by studies comparing food purchases with and without income management[15].

In 2015 the median equivalised gross weekly household income for NT Indigenous adults was $430, compared to the non-Indigenous equivalent of $1,247 and nationally the Indigenous income of $542. Non-Indigenous NT incomes benefitted from the Intervention, with a sustained jump in income between 2005 and 2008[16].

WHAT ABOUT THE CHILDREN?

The Intervention was said to be about the children. So how have they fared?

CHILDREN IN ‘WELFARE’: There are more children under ‘Welfare’ now than ever before. Between 2009 and 2015 care and protection orders more than doubled. In 2015 3.3% of Indigenous children in the NT were in out of home care, compared to 0.34% of non-Indigenous children in the NT, and 0.5% of Indigenous children nationally[17].

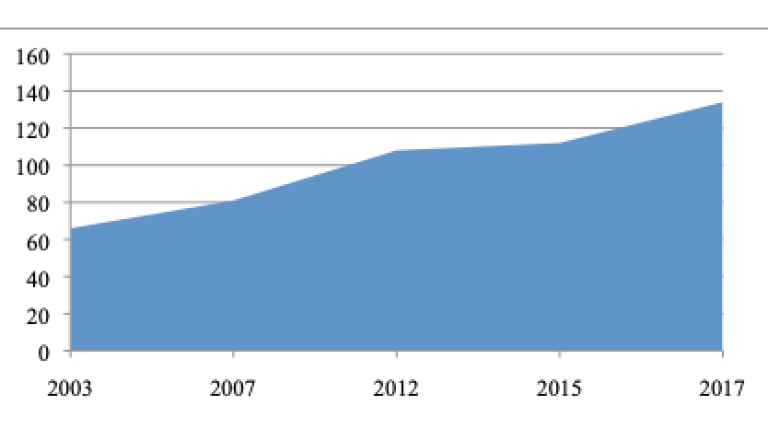

CHILD INCARCERATION IN THE NT: There are more children in prison in the than ever before. Generally, 100% of children in prison are Indigenous, and the clear majority have not yet been sentenced. While the rate of young people aged 10-17 (per 10,000) in detention on an average night in 2018 nationally was 3.47, in the NT the rate is 16.06.[18]. The yearly daily average population in detention has increased from 29 in 2006–07 to 49 in 2015–16, while the number of individual admissions into detention doubled in the ten years between 2006 and 2016[19].

The following graph shows the number of youth per 10,000 who were under supervision on an average day[20]:

Adults in Prison: Similarly, the age standardized imprisonment rate more than doubled for Indigenous adults between 2000 and 2016, while the non-indigenous rate more than halved.

SUICIDE IN CHILDREN: Suicide is the leading cause of death for children in the NT. The NT has Australia’s highest child suicide rate per capita for nine out of the last 10 years leading up to 2017 with the NT reporting 13.9 deaths per 100,000 persons. All other states and territories reported rates ranging from 1.7 to 3.6 deaths per 100,000.[21]

Suicide overall in the NT: In 1991 5% of suicides in the NT were of Indigenous people compared to 50% in 2010.[22] The NT appears to have the highest rate of suicide nationally. [23]

CONCLUSION

The Intervention/Stronger Futures legislation has been an abject failure, with living conditions and health negatively impacted since its introduction.

As the AIDA (Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association) Health Impact Assessment of the Intervention[24] stated: “It is simply not possible to fight oppression with oppression”

They predicted that “the intended health outcomes of the NTER (improved health and wellbeing, and ultimately, life expectancy) are unlikely to be fully achieved through the NTER measures. It is predicted that it will leave a negative legacy on the psychological and social wellbeing, on the spirituality and cultural integrity of the prescribed communities.”

Unfortunately, their predictions have come true.

People’s health and living conditions are in many cases worsening, and the gap is widening. More children than ever before are being taken from their families, in prison, and taking their own lives. Less children are at school.

When will governments learn that punitive interventions that target Aboriginal people still suffering from the intergenerational impacts of colonisation will not only fail, but further impoverish people?

The Intervention was said to be a response to the “Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle “Little Children are Sacred””[25] report. However, the first recommendation which is continuously ignored ended with the following statement:

“It is critical that both governments commit to genuine consultation with Aboriginal people in designing initiatives for Aboriginal communities”

Until this is done, and Aboriginal people manage their own affairs, there will be no closure of the gap.

[1] Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017 Report, AHMAC, Canberra.

[2] Brown A, McDonald M, Calma T. Acute rheumatic fever and social justice. Medical Journal of Australia. 2007;186(11): pp. 557-8.

[3] No Warlpiri, no school? A preliminary look at attendance in Warlpiri schools since introducing the First Four Hours of English policy. Greg Dickson. Ngoonjook: a Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, no. 35, 2010, pp. 97–113

[4] https://www.smh.com.au/education/welfare-stick-fails-for-nt-schools-20111221-1p5op.html

[5]AIHW, 2018, and School attendance and retention of Indigenous Australian students Issues Paper No 1 produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse Nola Purdie and Sarah Buckley, September 2010

[6] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-12-06/indigenous-school-attendance-going-backwards/9230346

[8] https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/reports/closing-the-gap-2018/employment.html

[9] Better than welfare? Work and livelihoods for Indigenous Australians after CDEP. Edited by Kirrily Jordan. ANU Press. 2016

[10] Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017 Report, AHMAC, Canberra

[11] Altman,J. The debilitating aftermath of 10 years of NT Intervention, Land Rights News. Northern Edition July 2017

[12] ibid

[13] ibid

[14] ibid

[15] Brimblecombe, J., McDonnell, J., Dhurrkay, J. G., Thomas, D. P., & Bailie, R. S. (2010). Impact of income management on store sales in the Northern Territory: after the intervention. Medical Journal of Australia, 192(10), 549-554.

[16] Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017 Report, AHMAC, Canberra

[17] Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017 Report, AHMAC, Canberra

[19] Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory Chap 9, p 47

[20] derived from (i) Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council, 2017, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework 2017 Report, AHMAC, Canberraand (ii) https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/4a36815a-20d8-4545-9f7f-8e3c89ad9a24/aihw-juv-116-nt.pdf.aspx

[21] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-01-16/suicide-rate-in-territory-child-suicide-lifeline-warren-snowdon/10717718, and https://digitallibrary.health.nt.gov.au/prodjspui/bitstream/10137/7055/1/Northern%20Territory%20Suicide%20Prevention%20Strategic%20Framework%202018-2023.pdf

[24] Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association and Centre for Health Equity Training, Research and Evaluation, UNSW. Health Impact Assessment of the Northern Territory Emergency Response. Canberra: Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association, 2010

[25] Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle “Little Children are Sacred”, Report of the Northern Territory Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse. (2007) NT Government

This article was written by Hilary Tyler, a Pakeha from Aotearoa, living in Mparntwe for the past 14 years. A member of the Intervention Rollback Action Group and Shut Youth Prisons Mparntwe, and a doctor.